2 Tides

Understanding the tides is crucial for planning and carrying out safe sea kayak trips.

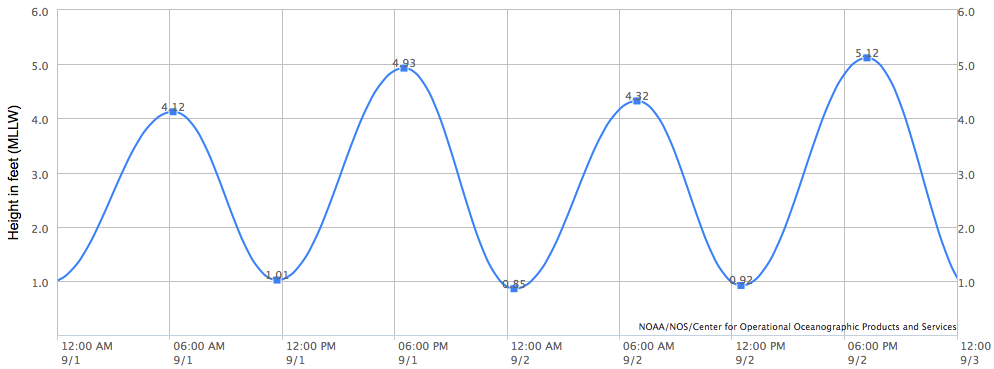

In some areas of the UK, the falling tide uncovers vast areas of seabed, making some channels unusable and possibly making launching and landing difficult. This can be particularly problematic around the Norfolk coastline and other areas with large shallow sand and mud flats.

The rise and fall of the tides creates flows known as ‘tidal streams’. 4 knot tidal streams are not unusual and some parts of the UK coastline experience 9 knot streams. Paddling against tidal streams can slow progress, or simply be impossible, so being able to predict them and account for them in trip planning is important.

2.1 What causes the tides?

2.1.1 The moon

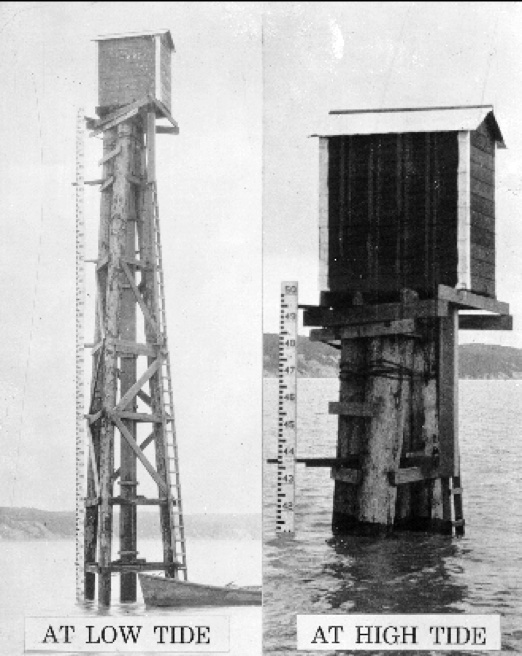

The principal cause of tides is the gravitational pull of the moon on the earth’s seas. The gravitational force exerted by the moon reduces with increasing distance. So, the seawater nearest the moon is pulled towards the moon more strongly than the earth, resulting in a high tide. On the opposite side of the earth, the seawater is attracted towards the moon less strongly than the earth, resulting in another high water. Low water occurs at the midpoints.

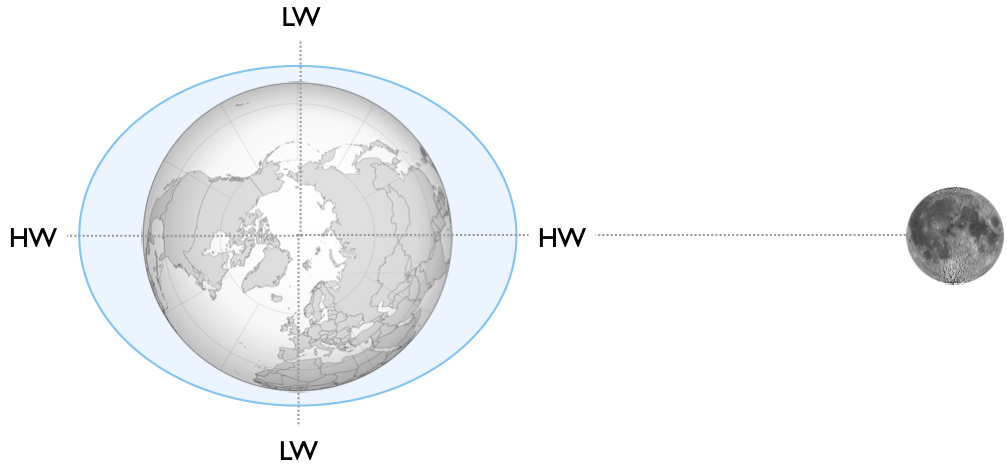

The earth rotates relative to the moon, causing the water level at each point on its surface to rise and fall.

In practice, this picture is highly simplified – the land disrupts this model of a perfect water-covered sphere. The reason we get two (often large) tides a day in the UK is to a large extent due to resonant effects in the Atlantic ocean and the concentration of tides due to the shape of the land. However, let us return to our simple water-covered sphere model….

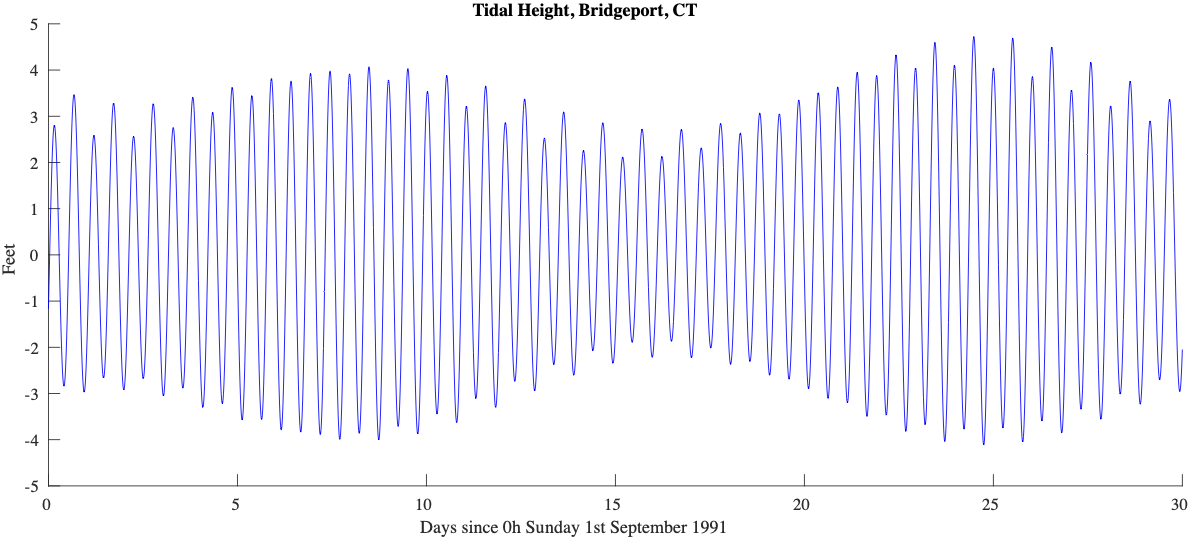

The earth rotates once every 24 hours. So, every 24 hours, a point on the earth should see 2 high waters and 2 low waters.

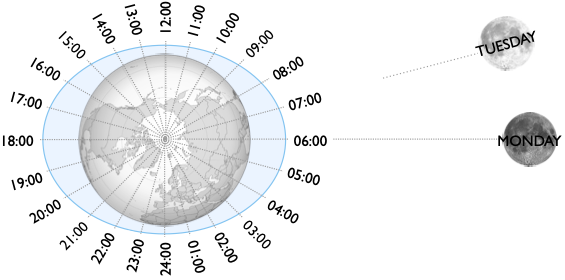

The moon orbits the earth on an approximately monthly cycle. So, once the earth has completed a full revolution, the moon will have moved a little. This has the effect of making high water occur about one hour later each day. The curve below shows typical tidal cycles over 2 days. Note that there are two high tides and two low tides each day. High water is around an hour later on the second day.

2.1.2 The Sun - neaps and springs

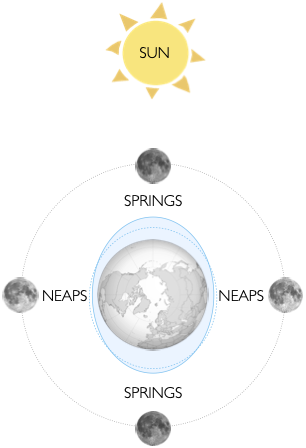

The sun is much further from the earth than the moon, but also much bigger. The net result is that it has a less significant, but still important, effect on the tides. When the sun and moon are in line, tides will rise higher and drop lower than if the sun and moon act perpendicular to each other.

The large tides caused by the combined pull of sun and moon are known as spring tides. The smaller tides caused by them pulling out of line are called neap tides. Note that spring tides are nothing to do with the seasons. They occur roughly every two weeks throughout the year about 1-2 days after each full or new moon. The time between spring and neap tides is about 7 days, so if you get big tides one weekend, expect smaller tides during the next one.

Tidal range is defined as the difference in the height of water between successive high and low waters. During a spring tide, the tidal range will be around twice that of a neap tide, so about twice as much water will be moving about.

There are also variations in the tidal range over the course of a year. In the UK, we often experience larger tidal ranges around the spring and autumn equinoxes because the angle of the earth’s rotation is square to the plane of the sun and the moon at that time (more detailed explanation here). The tidal range is also affected by:

The distance of the moon from the earth - this varies because the moon’s orbit isn’t a perfect circle. When spring tide coincides with the moon being close to the earth, the range will be especially large - this is called a ‘perigean springs’ - perigee being a term for the lowest part of an orbit. Spring tide ranges will be lower when the moon is furthest away - called the ‘apogee’ of the orbit - we call this an ‘apogean springs’ (more info here).

The distance of the moon from the sun - the sun’s orbits is also elliptical. The effect is smaller, but the tidal range is increased when the sun is closest to the earth - known as ‘perihelion’.

In practice, there are many other factors affecting the tides, making predicting times of high and low water a specialized science. The tide is modeled as a combination of sine waves, each with it’s own size and timing (phase). These have names like ‘M2’ - M2 is the twice daily effect of the moon that we described as the main cause of tides above. Of course, as the earth rotates the direction of the sun’s gravity changes on a daily basis, leading to a coefficient called ‘S2’. As the M2 and S2 waves drift in and out of phase, we see the emergence of neap and spring tides.

In addition there are around 35 other ‘tidal constituents’ would need to be considered for even a simple forecast. These relate to effects like:

The elliptical (not perfectly circular) orbit of the moon (N2) - causes apogean and perigean spring tides

The fact that the moon is not directly above the equator, and that this declination varies through its orbit (K1 and O1) - leads to big tides at the equinox

The tilt of the earth relative to the sun, leading to seasonal variations in the tide (Sa, Ssa)

The effects of shallow water on the movement of the tide (M4, M6, M8, S4)

Collection of data over extended time periods has made the prediction of the tide extremely accurate well into the future (i.e. years ahead) at important locations like major ports.

2.1.3 Meteorological effects

Not all tidal effects are driven by the sun and moon. The weather may have an effect too:

The height of the tide is affected by air pressure - a phenomenon known as the “inverted barometer effect”. Water levels are higher when air pressure is low and lower when air pressure is high. As a rule of thumb, the change is water level is around 1 cm per 1 hPa / 1 milibar pressure. The sea responds to atmospheric pressure over a large area, so changes in sea level due to air pressure rarely exceed 30 cm.

A strong onshore wind will tend to pile up water at the coastline, resulting in increased water levels - this effect is called ‘wind setup’. An offshore wind will do the opposite. Winds blowing along the coast may raise the sea level at high tide and depress it at low tide, increasing the tidal range. Winds blowing in one direction may also increase the length of time that a tidal stream flows in that direction.

Strong low pressure systems often bring strong westerly winds to the British Isles. As a result, the inverted barometer effect and wind setup often occur together. The resulting elevated sea level is called a ‘storm surge’.

2.2 Tide tables

The tide at ports is of significant interest to mariners and data exists on the height of tide going back many years. For example, data at https://www.bodc.ac.uk gives records of the tide at Newlyn in Cornwall going back to 1915. This data enables very accurate forecasts to be made of the times of high and low water at these locations, known as ‘standard ports’. Times of high and low water for standard ports are given in tide tables.

Tide tables are easy to use, but often report times in Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). During summer, when British Summer Time (BST) is in operation, an hour needs to be added to give the correct time. Some tide tables are given with the corrections for BST already applied - so always check if you’re using an unfamiliar tide table!

Tide tables are available from many sources. I find that the most useful are:

- The National Tide and Sea Level Facility: Accurate data for all major UK ports for the next 28 days.

- Easytide: UKHO site giving predictions 7 days ahead for practically anywhere in the world.

- Visit My Harbour: An impressive array of free tide tables for the whole of the current year.

Tide tables can, of course, be purchased in printed form. They also appear in nautical almanacs that are republished each year. I find it useful to obtain a copy of Reeds Small Craft Almanac each year so that I’m not reliant on an internet connection when I’m doing tidal planning.

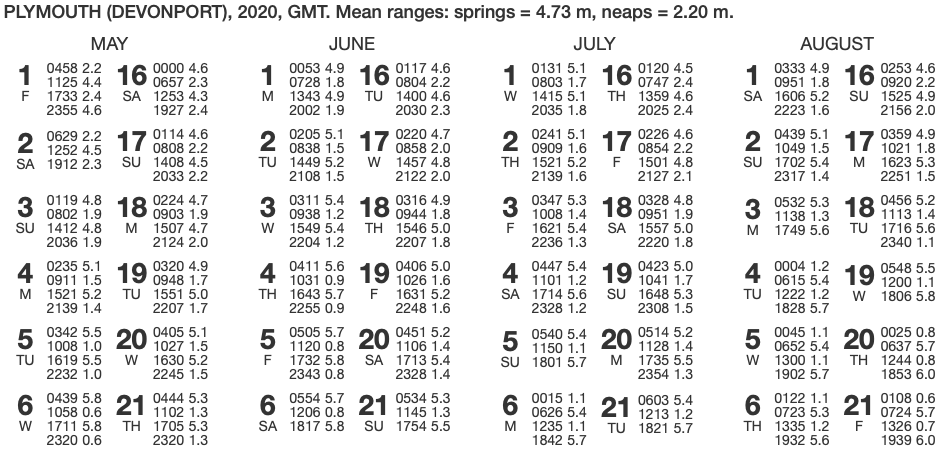

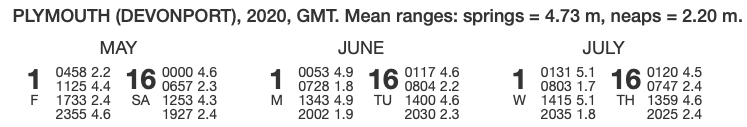

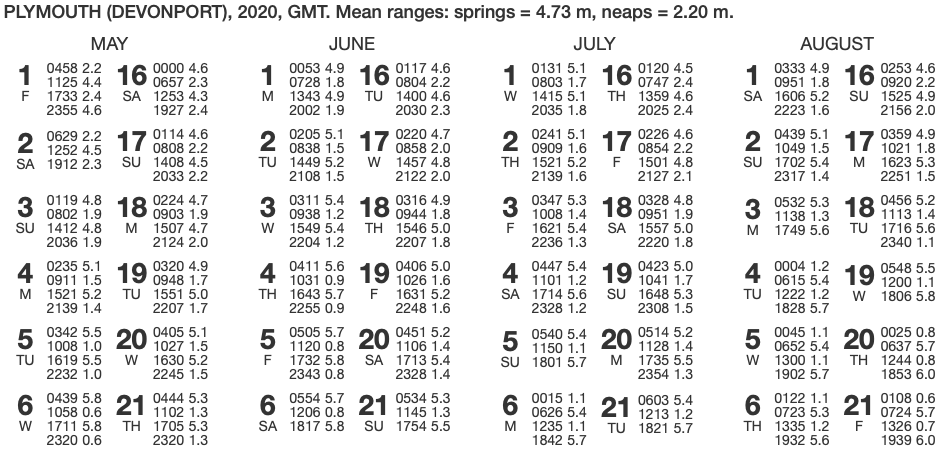

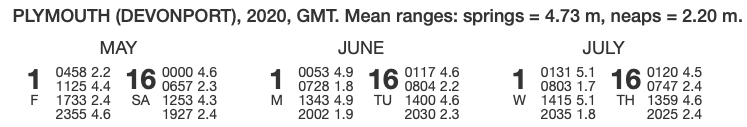

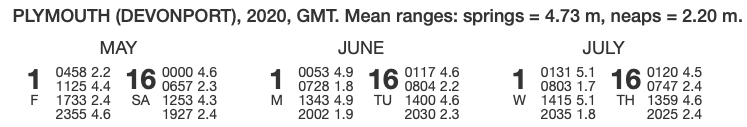

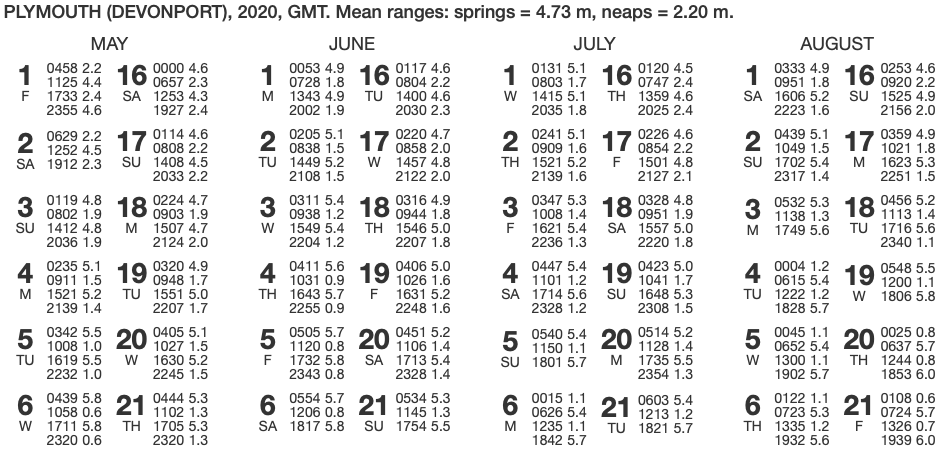

Find times of high and low water during the day at Plymouth on June 4th 2020. Also, find the tidal range.

Consult the tide table for Plymouth above. Note that times are given in GMT. Find the entry for June 4.

Big values of tidal height (5.6 m, 5.7 m) must refer to high water (HW). Low values (0.9, 0.9) refer to low water. So, during the day, the times are:

10:31 GMT 0.9 m Low water

16:43 GMT 5.7 m High water(we’re ignoring the early morning high tide and the late night low tide)

Being June, British Summer Time (BST) is in operation. To convert to BST, we must add one hour to the times given:

11:31 BST 0.9 m Low water

17:43 BST 5.7 m High waterThe tidal range is the difference in height of tide between high and low water: 5.7 - 0.9 = 4.8 m.

To plan paddles in areas affected by tides, we’ll likely need additional information not in tide tables - for example from guide books, charts and nautical almanacs. We’ll look at how to use this information in subsequent sections of these notes.

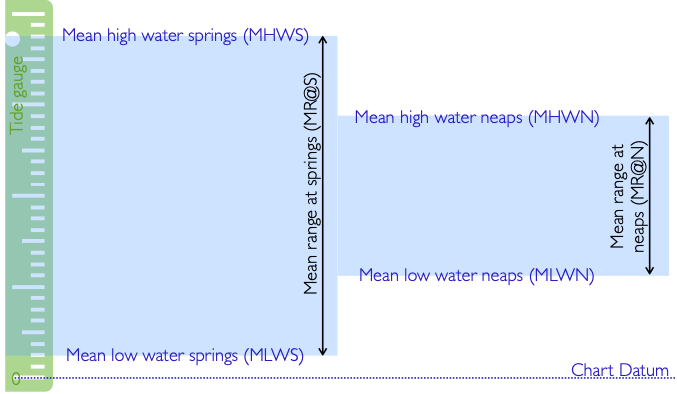

2.2.1 Tidal range

The tidal range is simply the difference in the height of the tide between high water and low water. Some parts of the world have a small tidal range - like the South Devon and Dorset coasts (up to 3m), whilst others have large ranges, like the Bristol channel (up to 14.4 m). In general, you’ll need to pay more attention to planning for the tides in areas with larger tidal ranges.

It is often useful to know whether the tide is a spring tide, a neap tide or somewhere in between.

Simply inspecting the tide table can give some information - spring tides will be associated with higher high waters and lower low waters. Some tide tables will indicate the days on which spring or neap tides occur.

2.2.2 Tidal factor*

I find it useful to calculate a tidal factor – the ratio of today’s tidal range to the typical tidal range for a spring tide. This will be 1 (or 100%) for a typical spring tide and about 0.5 (or 50%) for a typical neap tide. Calculating this is straightforward, but a calculator can be handy:

Factor = tidal range today / tidal range at mean springs

For example, if the tidal range today is 6 meters and the tidal range at mean springs is 8.3 meters, then the factor is 6/8.3 = 0.72 = 72%

Data on the tidal ranges at mean springs can be found:

- In the back of Pesda Press’s sea kayak guidebooks.

- At https://www.ntslf.org (under ’highest & lowest predicted tides) - you’ll need to subtract mean low water springs from mean high water springs to get the mean spring range

- In any nautical almanac (e.g. The Reeds Small Craft Almanac)

For example, the mean tidal ranges at springs and neaps are given at the top of the tide table below:

What is the tidal factor on June 1st 2020?

On June 1st, we have the following tidal data for Plymouth (adding an hour for BST):

08:28 BST Low water 1.8 metres

14:43 BST High water 4.9 metresThe tidal range on July 4th is 4.9-1.8 = 3.1 metres.

The mean range at springs for Plymouth is 4.73 metres. So the tidal factor is 3.1/4.73 = 0.66 = 66%.

The tidal factor is 66%, which is part way between neaps (50%) and spring (100%), but closer to neaps than springs.

2.3 Tidal streams

In order for the tide to rise and fall at a given location, water must move from one place to another. These horizontal movements of water are known as tidal streams.

In many areas frequented by sea kayakers, steep rocky coastlines make the height of tide less of a concern. However, tidal streams often run at 2-3 kt and sometimes much faster. Given that tidal streams can move as fast as we can paddle, they clearly need to be accounted for in our plans.

We may choose to arrive at areas with fast tidal flows (typically headlands or narrow straits):

At slack water to avoid the tidal flow to increase safety (or perhaps to remain within our leadership remit)

At full flow to maximize the benefit from the tidal stream, and to enjoy crashing through the race waves

As the tide builds, so that we can gain confidence playing in the stream and stop when it gets too much for us.

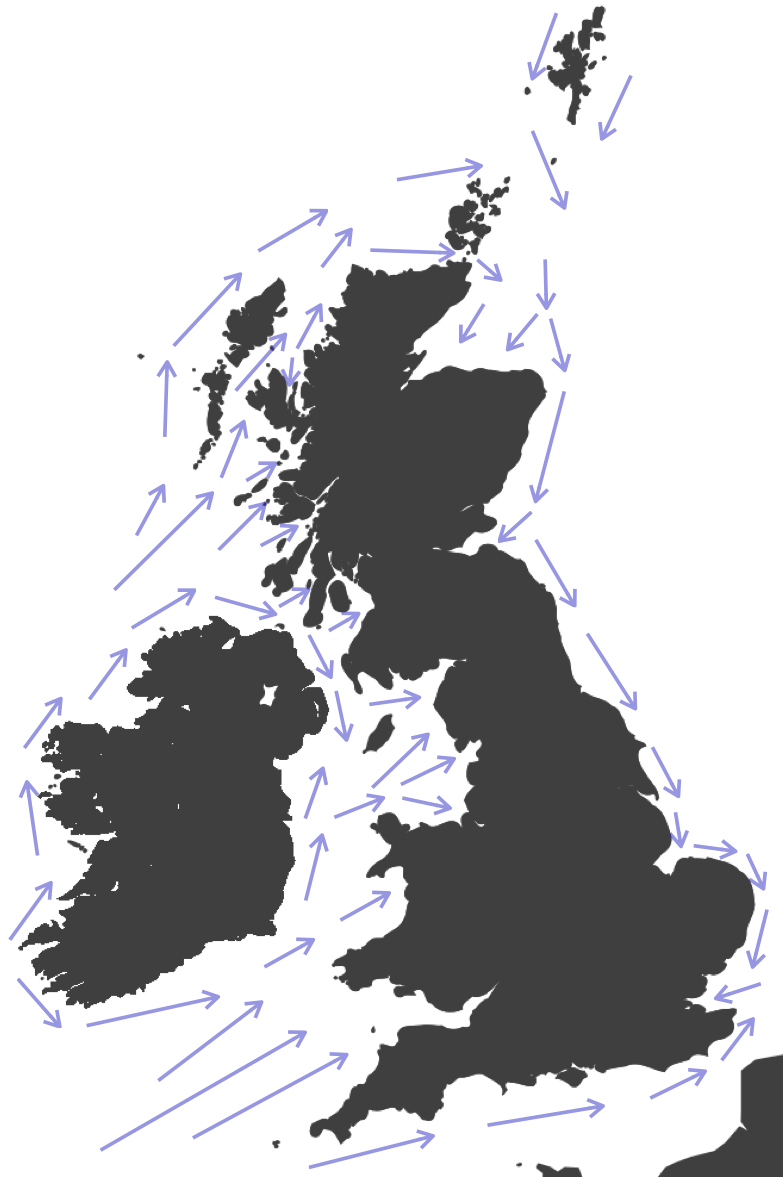

This map below shows the directions of the main flood tidal streams (i.e. those that occur in the run up to high water at Dover and Liverpool) around the UK. The tidal streams run in the opposite direction during the ‘Ebb’.

Unfortunately, tidal streams do not necessarily change direction at high and low water, so we need to find information on when they turn for the location at which we want to paddle. A range of information sources about tidal streams exist. The main sources are:

- Tidal diamonds (and the associated tables) on charts

- Tidal stream atlases

- Pilots and guidebooks

These sources will give the time that the tide changes relative to some reference port. Note that the reference port used may be some distance from the location - e.g. Dover is used as a reference port by some sources for tidal streams at Lands End.

Each type of source presents the information in a different way, so we’ll consider them one by one in the sections that follow.

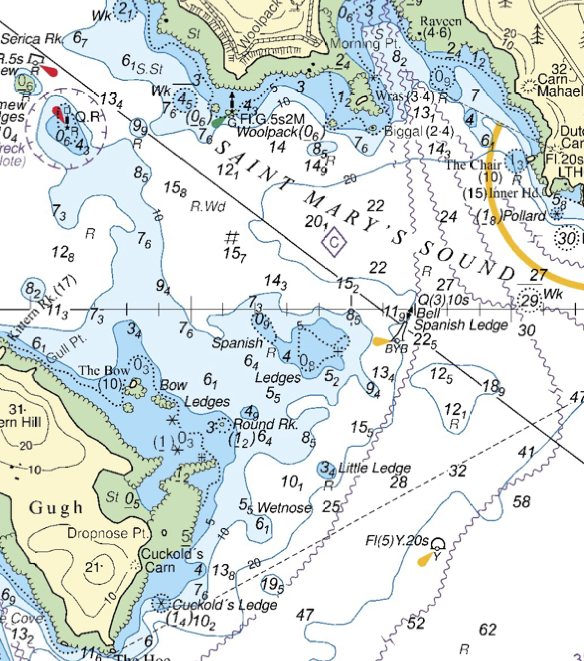

2.3.1 Tidal diamonds

On charts, tidal information is given at specific points denoted by a purple diamond shape with a letter. A table, normally found at a corner of the chart, gives information on the tidal flow at each point.

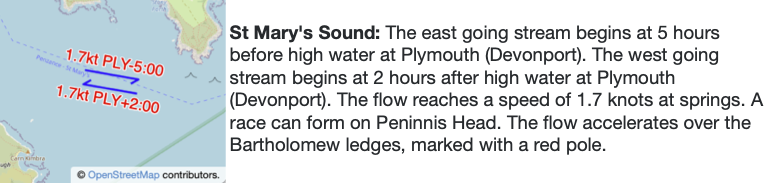

The chart extracts below show Saint Mary’s Sound in the Scillies and the corresponding data table. The information is laid out in a fairly self-explanatory way:

Describe the tidal flow in Saint Mary’s Sound on July 4th 2017? We notice that the tidal stream tables refer to high water at Plymouth. We must begin by consulting a Plymouth tide table:

On July 4th, we have the following times of high and low water, remembering to add the hour for British Summer time:

05:47 5.4 m High Water

12:01 1.2 m Low Water

18:14 5.6 m High WaterWe note that the tidal range is 4.4 m, and the factor is 4.4/4.73 = 93%, which is close to springs. We will use the left hand column for diamond C which gives the rates at spring tides.

The table below shows data taken from tidal diamond C related to times on June 14. It has been created by entering the HW times for Plymouth on the ‘0’ row then counting backward and forward up and down the table:

| Time relative to HW | Bearing | Time of day | Rate | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -6 | 300 | 12:14 | 0.4 kt | |

| -5 | 20 | 13:14 | 0.1 kt | Tide is turning to the east |

| -4 | 109 | 14:14 | 0.7 kt | |

| -3 | 110 | 15:14 | 1.2 kt | |

| -2 | 111 | 16:14 | 1.5 kt | |

| -1 | 111 | 17:14 | 1.6 kt | |

| 0 | 111 | 05:47 , 18:14 | 1.7 kt | Tide runs at maximum speed east |

| +1 | 125 | 06:47 | 1.5 kt | |

| +2 | 190 | 07:47 | 0.1 kt | Tide is turning to the west |

| +3 | 275 | 08:47 | 1.3 kt | |

| +4 | 272 | 09:47 | 1.7 kt | Tide runs west at maximum rate |

| +5 | 265 | 10:47 | 1.0 kt | |

| +6 | 292 | 11:47 | 0.7 kt |

So, the tide starts flowing west a little after 07:47 in the morning. At around 09:47, it reaches a maximum speed in the westward direction of 1.7 knots. The speed drops until around 13:14, when the tide swings to the north, before starting to run east. It reaches the maximum speed eastward of 1.7 knots at around 18:14 in the evening.

Note the approximate times given – we only have data at each hour, so we can only estimate the times of slack water and maximum flow.

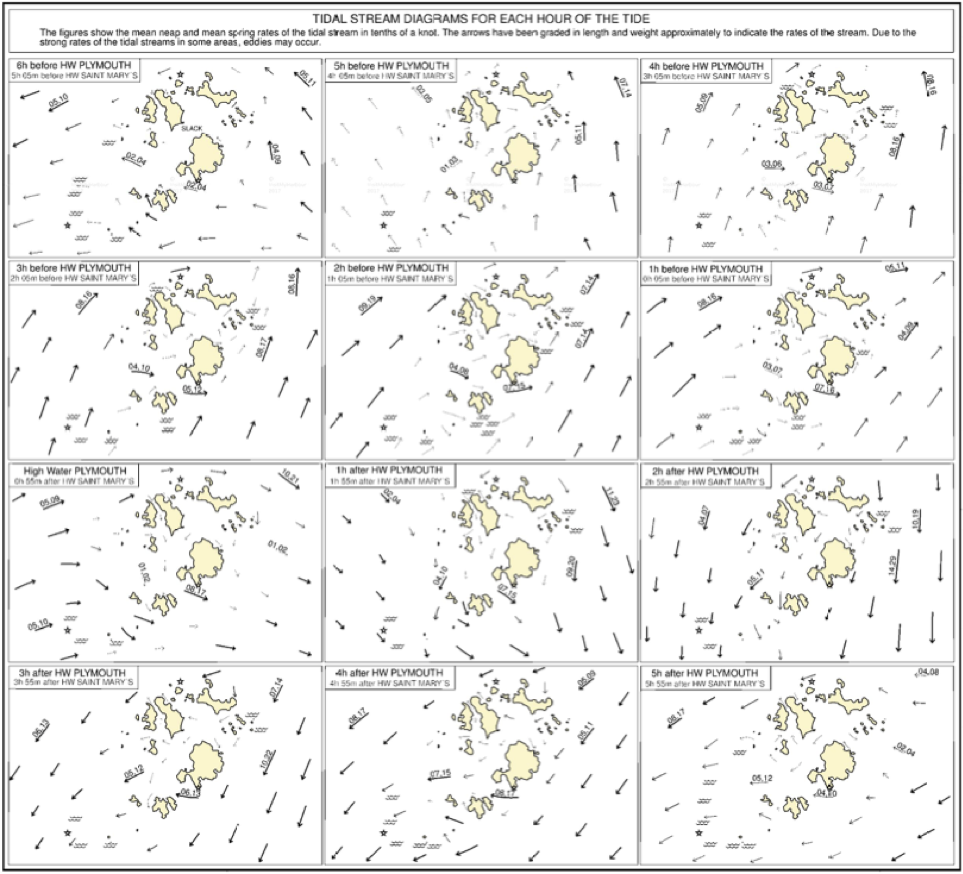

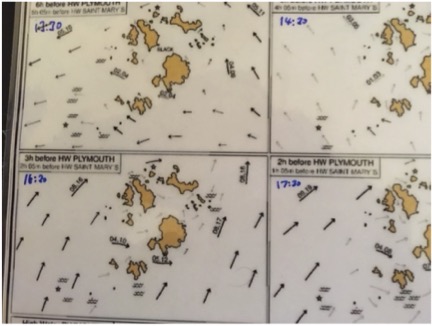

2.3.2 Tidal stream atlases

The UKHO publishes a series of tidal stream atlases that cover the UK. Atlases for smaller areas are sometimes found on nautical charts. Atlases can be found from other sources (e.g. in Reeds Almanac), but these are normally from UKHO data. Exceptions include a couple of standalone books published by local yachtsman covering specific areas of popular coastline and going into great local detail. Excellent flow atlases are also found in some pilot books.

Visit My Harbour is a great source, providing all the main UKHO tidal stream atlases for free.

A tidal stream atlas is a series of maps that show tidal flows at different times in a tidal cycle:

The thickness of arrows on an atlas gives an approximate indication of tidal speed. When numbers are shown, they are in tenths of a knot, with a comma separating flow speeds for springs and neaps.

Tidal stream atlases can be of limited use for inshore kayaking, although there are many areas where they are very useful – especially around island archipelagos like the Scillies, Orkney and the Channel Islands.

A good way to use an atlas is to mark it up with the timings for the day to get a feel for what the tide is going to do across the area, as shown below:

2.3.3 Pilots and guidebooks

Tidal diamonds and detailed tidal atlases are not available for all areas. Often, we must rely on less complete data given in narrative form from local experts. Such data can be found in sailing directions, books that are written to convey local knowledge to mariners. These are colloquially know as ‘pilots’. The UKHO publishes a range of pilots covering the UK in detail and the rest of the world in less detail. Other national agencies do the same. The information in these pilots is primarily intended for large ships, so yachtsman have produced their own pilots, often with more detailed information, for areas in which they cruise. These are often useful for kayakers.

Sea kayaking guidebooks include the most important tidal information from pilots and other sources. Being focused on kayaks, rather than large ships or yachts, they’re a great source of information in a compact format. Over the last few year, Pesda Press has published an excellent set of guidebooks covering most of the UK. For most kayakers, these books will be cheaper, more accessible and better than UKHO or yachting pilots.

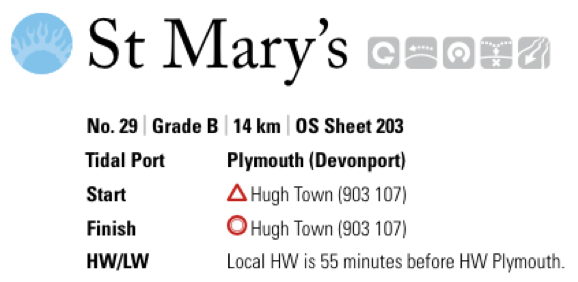

All pilots use a similar format for describing tidal streams. In sea kayak pilots you will also see tidal stream data shown graphically on maps:

Pilot information is presented in a fairly understandable format. Its use is best illustrated by an example.

Describe the tidal flow in Saint Mary’s Sound on June 14th 2017 (HW Plymouth is at 09:29 BST and 21:44 BST)?

We already know that HW Plymouth is at 09:29 BST and 21:44 BST.

The ESE stream begins HW Plymouth -5:00

09:29 – 05:00 = 04:29 BST

21:44 – 05:00 = 16:44 BST

The WNW stream begins HW Plymouth +2:00

09:29 + 02:00 = 11:29 BST

21:44 + 02:00 = 23:44 BSTSo, we expect the tide to run ESE in the morning (from 04:29), turning WNW at 11:29. It turns ESE again at 16:44, running in this direction until 23:44.

2.4 Paddling with tidal flow: Predicting speeds of tidal streams

2.4.1 Changes between neaps and springs*

We have focused so far on determining which way the tidal stream will be flowing and when. This is often enough to plan a simple sea kayak journey. However, it is sometimes useful to estimate the speed of the tide with greater precision.

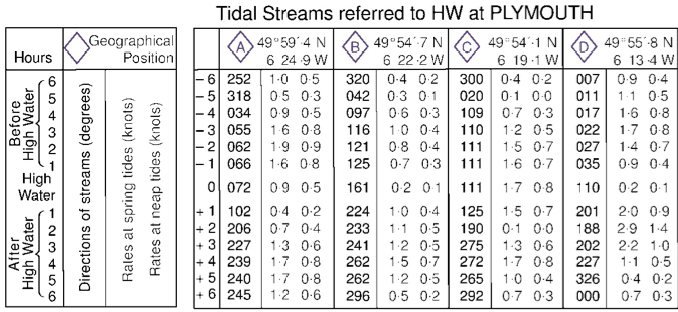

Information from either tidal diamonds or a tidal stream atlas can give information on flow speeds at springs and neaps for each hour. What if it isn’t springs or neaps?

There are two methods to calculate tidal flows – using factors and using interpolation. Factors are quicker, but interpolation may be a little more accurate.

We calculated a tidal factor earlier as the ratio between the actual tidal range and the range at mean springs. Given that the tidal range is what drives the tidal streams, we can simply multiply the factor by the flow speed at springs to estimate the speed that we will experience.

What will the maximum flow be in St. Mary’s Sound on 1 June 2020?

We previously consulted a tidal diamond (and a pilot) and found that maximum flow speed in the Sound is 1.7 knots at springs (and 0.8 knots at neaps).

Consulting the Plymouth tide table….

The tidal range on June 1st is 4.9-1.8 = 3.1 meters. Given that the mean range at springs is 4.73m, the factor is 3.1/4.73 = 0.65 - i.e. between springs and neaps.

We estimate the maximum flow as 0.65 X 1.7 = 1.1 knots.

Interpolation The method of interpolation uses both the springs and neaps flow speeds and associated tidal ranges to calculate flow speed at an intermediate tidal range. This can be done using an equation or graphically. The equation is:

\[ speed@neaps+\left(speed@springs-speed@neaps\right)\frac{range-range@neaps}{range@springs-range@neaps} \]

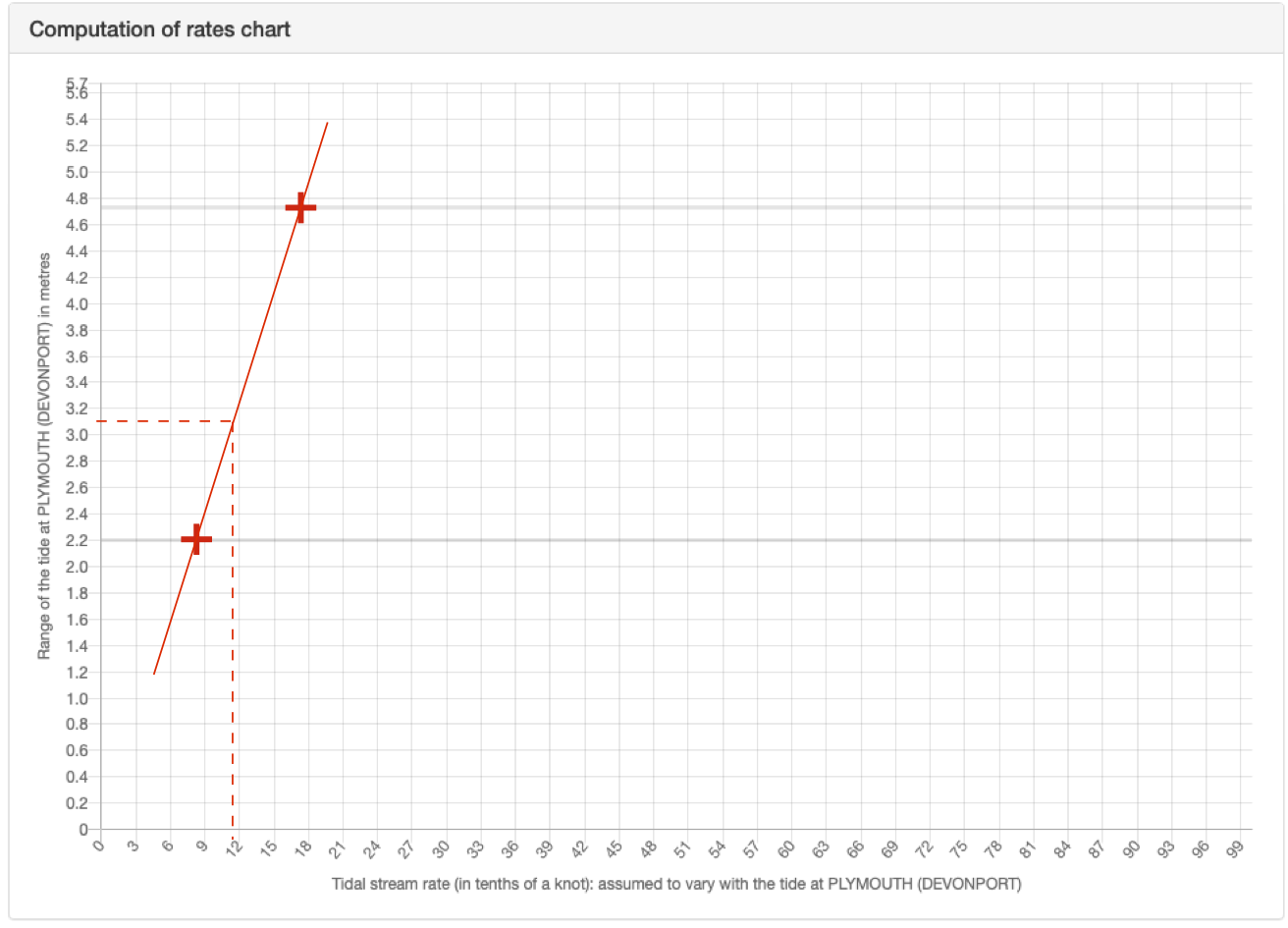

Using this is clearly a pain, so the calculation is more commonly done graphically using a plot found on the inside cover of a tidal stream atlas:

Tidal stream flows for both springs and neaps are plotted on this diagram against the corresponding tidal ranges – mean springs and neaps ranges being shown on the diagram. A straight line is drawn between these two points. This line can be used to calculate a speed for any given tidal range. An example will help explain:

Estimate the fastest speed of tidal flow in Saint Mary’s Sound on 1 June 2020?

We previously consulted a tidal diamond and found that maximum flow occurs at HW Plymouth and 4 hours later and is 1.7 knots at springs, 0.8 knots at neaps.

We also know from the tide tables that:

range at mean springs = 4.73 m

range at mean neaps = 2.20 m

Note that these correspond to the position of the dotted lines on the computation of rates chart, as we would expect. The tidal range on June 1st is 3.1 m.

USING THE EQUATION:

Speed = speed@neaps + (speed@springs - speed@neaps)X(range - range@neaps)/(range@springs - range@neaps)

Speed = 0.8 knots + (1.7 knots – 0.8 knots)X(3.1 m – 2.20 m)/(4.73 m – 2.20 m)

Speed = 0.8 knots + 0.9 knotsX 0.9 m/2.53 m

Speed = 0.8 knots + 0.32 knots = 1.1 knots

USING THE DIAGRAM:

Mark the speed at springs (1.7 knots) on the upper grey horizontal line, (upper red cross). Similarly, mark the speed at neaps (0.8 knots) on the lower horizontal line (lower red cross).

Draw a straight line (non-dashed red line) between these two crosses.

Draw a horizontal line across from the tidal range on June 1st (3.1 m) (horizontal dashed red line). Where this meets the line drawn previously, draw a final line down vertically. This goes to around ‘11’, indicating 1.1 knots.

2.4.2 Variation of flow through the tidal cycle*

Pilots will often only give a flow speed at springs, leaving us with the factors method as the only option for estimating flow speed at other tidal ranges. When spring and neap rates are quoted, interpolation can also be used.

Another problem with pilots is that they typically only provide data on when the direction of flow changes (slack water) and what the maximum flow is. We may wish to estimate flow at other times. Two rules of thumb exist to do this – the 50/90 rule and the rule of thirds.

2.4.3 50/90 rule*

The 50/90 rule states that:

- We expect zero flow speed as the tidal stream changes direction (slack water)

- One hour later, the flow attains 50% of maximum speed

- Two hours after slack water, the flow attains 90% maximum speed

- Three hours after slack water, the flow speed is a maximum (100%)

- 90% at 4 hours

- 50% at 5 hours

- Slack water occurs again after 6 hours

It’s fairly obvious that the flow is zero at slack water and maximal 3 hours later. And it’s intuitive that the flow speed decreases in hour 4 and 5 the same way it increased in hours 1 and 2, so the main point to remember is:

50/90 rule: flow attains 50% of max speed after 1 hour, 90% after 2 hours

Let’s look at an example:

Estimate how the tide will vary in Saint Mary’s Sound on 1 June 2020

The pilot tells us:

St Mary’s Sound: The east going stream begins at 5 hours before high water at Plymouth (Devonport). The west going stream begins at 2 hours after high water at Plymouth (Devonport). The flow reaches a speed of 1.7 knots at springs.

Consulting the Plymouth tide table….

The tide times at Plymouth on June 1st are:

01:53 BST 4.9 m HW

08:28 BST 1.8 m LW

14:43 BST 4.9 m HW

21:02 BST 1.9 m LWAs we’ve previously calculated: the tidal range is 4.9 m - 1.8 m= 3.1 m, giving a factor of 3.1 m / 4.73 m = 0.65, so maximum flow on June 1st = 0.65 X 1.7 knots = 1.1 knots.

Looking now at the afternoon high water, and recalling the pilot tells us that “The east going stream begins at 5 hours before high water at Plymouth (Devonport). The west going stream begins at 2 hours after high water at Plymouth (Devonport)”:

14:43 BST 4.9 m HW - 5 hrs = 09:43 : E going stream starts

14:43 BST 4.9 m HW + 2 hrs = 16:43 : W going stream startsSo, the east going stream will begin at 14:43 -5:00 = 09:43 and run until the west-going stream starts at 14:43 +2:00 = 16:43. We use the 50/90 rule to estimate the flow speeds. Unfortunately, the flow here runs for 7 hours, so we modify the rule slightly with 2 hours of 100% flow rather than one:

| Time | Compared to slack water | 50/90 rule | Flow speed | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 09:43 | 0 | 0% | 0 | - |

| 10:43 | +1 | 50% | 0.6 kt | E |

| 11:43 | +2 | 90% | 1.0 kt | E |

| 12:43 | +3 | 100% | 1.1 kt | E |

| 13:43 | +4 | 100% | 1.1 kt | E |

| 14:43 | +5 | 90% | 1.0 kt | E |

| 15:43 | +6 | 50% | 0.6 kt | E |

| 16:43 | 0 | 0% | 0 | - |

2.4.4 Rule of thirds

The rule of thirds is used to estimate average tidal flow speed during each hour. This makes it less useful in estimating flow at a given time, but more helpful if we are trying to estimate average speeds of paddling with tidal assistance (or hindrance). It states that:

- During the first hour after slack water, average flow is 1/3 of maximum

- During the second hour, average flow is 2/3 maximum

- During the third and fourth hours, average flow is equal to the maximum

- During the fifth hour, 2/3 maximum

- During the sixth hour, 1/3 maximum

Again, it’s fairly easy to remember that flow is at a maximum during the third and fourth hours and that the flow speed decreases in hour 5 and 6 the same way it increased in hours 1 and 2, so the main point to remember is:

Rule of thirds: the average flow is 1/3 of max speed in the first hour of the tide, 2/3 in the second hour

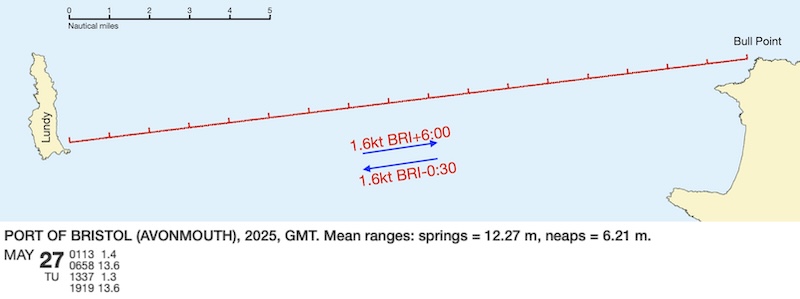

You are planning a trip from Bull Point to Lundy Island, a distance of about 17 miles, on May 27th 2025

If you depart at the start of the ebb tide, when do you expect to arrive?

On May 27th, high water is 06:58 GMT. For simplicity, we’ll call this 07:00 GMT = 08:00 BST. This is our departure time from Bull Point.

The range is 13.6-1.3 = 12.3 m, which matches the spring range closely, so we will assume that we can use the spring tide flow rate of 1.6 knots directly.

We will assume that our group paddles at 3 knots in still water. So:

During the first hour, the flow is 1.6/3= 0.5 knots, so our total speed is 3+0.5=3.5 knots, and we will cover 3.5 miles by 09:00

During the second hour, the flow is 2X1.6/3=1.1 knots, so our total speed is 3+1.1=4.1 knots and we cover 4.1 miles. We’ve now covered 3.5+4.1 =7.6 miles by 10:00

During the third hour, the flow is 1.6 knots, and our total speed is 4.6 knots, so we’ve covered a total of 12.2 miles by 11:00

During the fourth hour, the flow is 1.1 knots, total speed 4.1 knots, so we cover 16.3 miles by 12:00

During the fifth hour, the flow is 0.5 knots, total speed 3.5 knots, so we would expect to cover the remaining 0.7 miles in 0.2 hours = 12 minutes

So, we expect to arrive around 12:12 at Lundy (this is overly exact - perhaps we should say ‘12:15’). In reality the tidal streams will vary over this distance in ways that we don’t have information on.

2.5 Depth of tide

2.5.1 Predicting high and low water*

We saw in the last section how to use a tide table.

Such detailed data is not available everywhere that we would wish to paddle. To overcome this problem, reference books quote tidal constants for other locations. These are either added or subtracted to times of high and low water at standard ports to give local high and low water times. For example, this extract from a paddling guidebook tells us when HW and LW will occur at a location in the Isles of Scilly.

Find times of high and low water at St. Mary’s during the day on June 1st 2020.

Using the tide table, we can find the times of high and low water at Plymouth - ignoring the high water in early morning, and the low water late at night and remembering to add an hour for British Summer Time:

08:28 BST High water Plymouth

14:43 BST Low water PlymouthWe are told that HW and LW occur 55 minutes earlier than they do at Plymouth. Subtracting 55 minutes from the Plymouth times gives:

07:33 BST HW ST MARYS

13:48 BST LW ST MARYS2.5.2 Determining heights of high and low water*

2.5.3 Estimating the depth of the tide

So, we can find out the times and heights of high and low water. But what if we are interested in the height of tide at a different time in the tidal cycle?

Skippers of yachts and captains of big ships are very interested in accurate predictions of the depth of the tide, and use tidal curves from nautical almanacs to get a precise answer. Sea kayakers rarely need such precision - but it’s helpful to remember that the tide rise (or falls) slowly in the first and last hours after/before high/low water, and rises/falls quickly in the middle hours between high and low water.

The rule of twelfths gives us a little more precision:

The tide rises (or falls):

1 twelfth of it’s range in the first hour after high/low water

2 twelfths in the second hour

3 twelfths in the third hour

3 twelfths in the fourth hour

2 twelfths in the fifth hour

1 twelfths in the sixth (final) hour

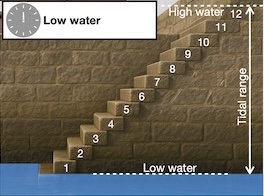

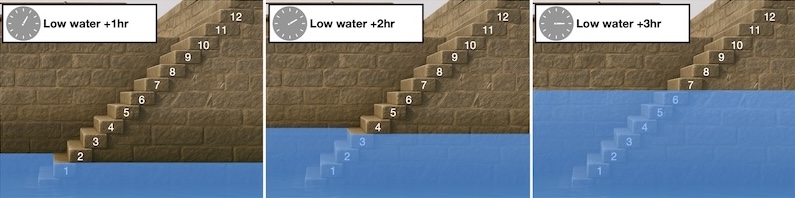

To make this a bit more real, let’s consider a slightly contrived example. Imagine a harbor that has 12 steps up the harbor wall:

Low water today is at 12:00, and at low water, the water level is at the bottom of the first step. It just so happens that high water today will be at the top of step 12, 3.6 m higher. So, a twelfth of the tidal range is 3.6 m/12 = 0.3m = 30 cm = the height of one step.

Let’s see what happens after each subsequent hour.

After the first hour, at 13:00, the tide has risen 1/12 of it’s range - one step.

In the second hour (14:00), it rises a further 2 steps (2/12 of the range) to the top of step 3.

In the third hour to 15:00, the tide rises 3 steps (3/12 of the range) more, to the top of step 6.

After the fourth hour, at 16:00, the tide rises 3 steps more to the top of step 9

After the fifth hour, at 17:00, the tide rises 2 more steps to the top of step 11

After the sixth hour, at 18:00, it is high water, and the water has risen a further 1 step to reach the top of step 12

Let’s look at a more practical example.

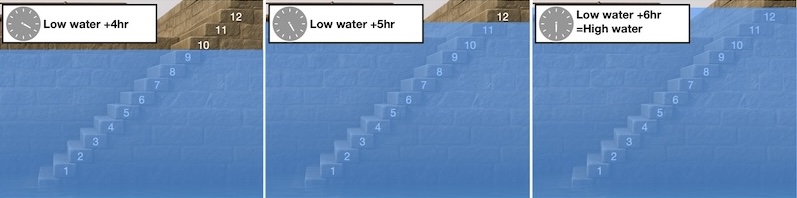

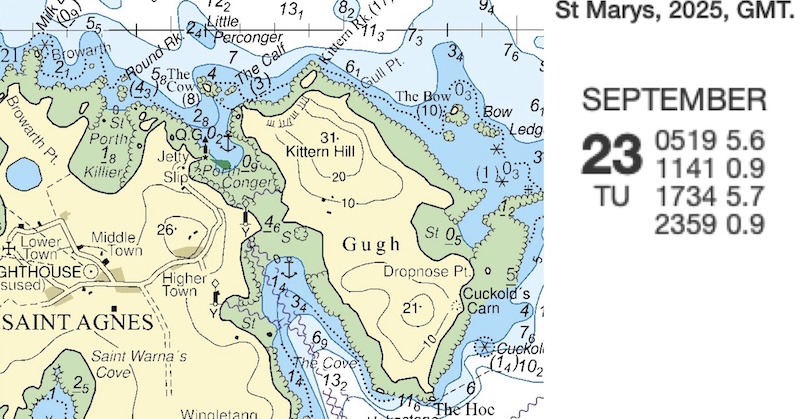

You would like to paddle the drying channel between Saint Agnes and Gugh on the afternoon of September 23rd 2025. At what time will the channel be underwater?

St. Mary’s harbor is very close to Gugh, so we can use the St. Mary’s times and heights without adjustment. We see that on the afternoon of the 23rd September, the low water height in 0.9 m and the high water height is 5.7 m, so that the tidal range is 5.7-0.9=4.8 m.

As we will be using the rule of twelfths, we will need to calculate 1/12 of 4.8m=0.4m

It is clear that the channel will only cover near the top of the tide, so we use times from high water. We note that the tide table is in GMT and 23rd September is in British Summer Time, so we must add one hour, giving a high water time of 18:34 BST, so:

At 18:34, the height of tide is 5.7 m (from tide table)

At 17:34, the height of tide is 1/12 of the range lower = 5.7-0.4= 5.3 m

At 16:34, the tide is 2/12 lower again = 5.3-2X0.4= 4.5 m

So, we expect the sandbar across the channel to cover just after 16:34, and be well covered by 17:34.

Chart © Crown Copyright and/or database rights. NOT FOR NAVIGATION. Reproduced by permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office and the UK Hydrographic Office (www.GOV.uk/UKHO)

2.6 Environmental considerations

2.6.1 Behavior of tidal streams

Tidal streams vary in strength according to the shape of the coastline and the seabed topography. With practice, it is possible to guess where the strong streams will occur and where the streams will be less strong, or eddies will form.

Flow tends to be weak close to the shore and stronger offshore. Flow at headlands that project into the tidal stream and squeeze it can be strong. Especially strong flows can occur in narrow channels between islands.

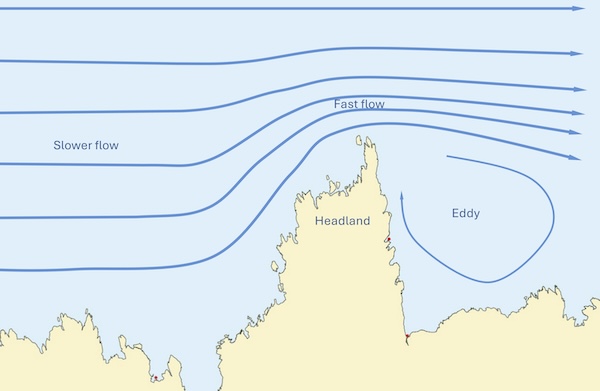

The flow of tidal streams is similar to that of a river, but on a much larger scale. Tidal flows tend to go in straight lines over long distances, taking lots of space to turn corners. An abrupt corner in a coastline will hence usually have an eddy behind it, where the flow is weak and may even be in the opposite direction to the main stream.

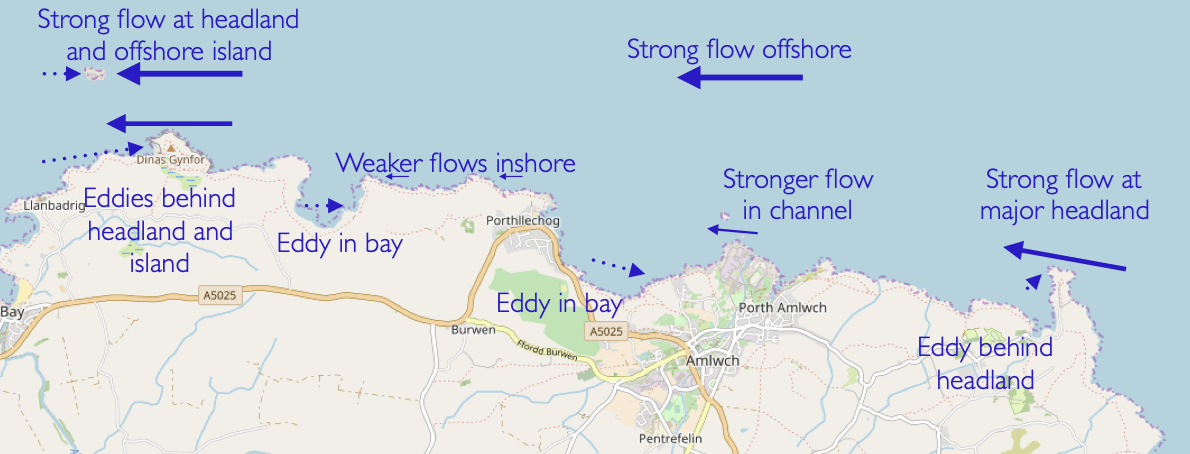

The map below show some of the local tidal stream effects that occur on the North Coast of Anglesey:

Anglesey sits at the NW corner of Wales. The tidal flow is concentrated here, as the water rushes around this corner towards Liverpool.

Zooming out and looking at Anglesey with a flood tide, it should be no surprise that the fastest flows are found at the major headlands on the N and NW side of the island and in the narrow part of the straits that separate the island from Wales.

2.6.2 Races and overfalls

If the tidal stream is squeezed into a smaller channel, it will speed up. This can occur in two ways:

The tidal stream can be squeezed sideways - perhaps into a narrow channel between islands, or by a headland protruding from the coastline:

The area of fast flowing water here is known as a tide race.

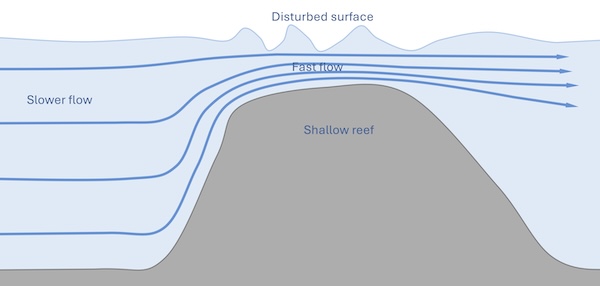

The tidal stream might be squeezed vertically by an area of shallow seabed, or a reef:

In this case, the area of fast flowing water is called an overfall.

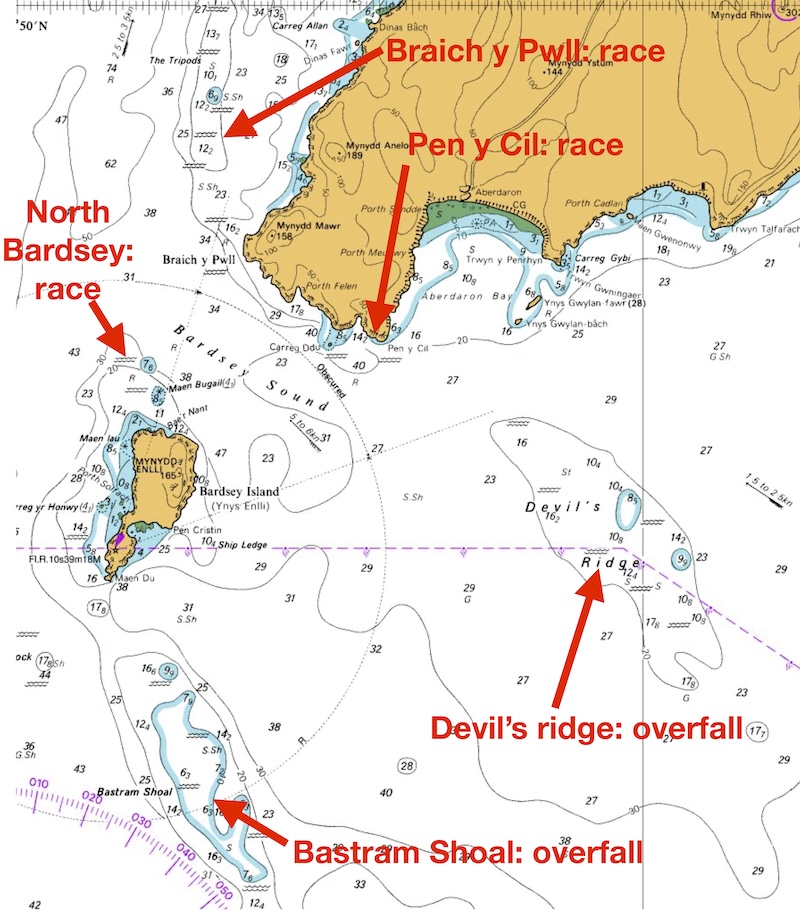

Identify races and overfalls in the area around Bardsey Sound

Bardsey sound is at the tip of the Lleyn Penninsula, a long finger of land sticking out into the sea. We shouldn’t be surprised that the tidal streams are strong at the end of such a big headland.

The chart makes it easy to see where major races and overfalls occur - they’re marked with wiggly lines that look like waves.

Two areas of shallows where overfalls form are marked: The Devil’s Ride and the Bastram Shoal. The tide speeds up over these shallow reefs, often causing a confused sea state.

There are a number of races marked around Bardsey sound where land squeezes the tidal stream - at the north end of Bardsey, at Pen y Cil and at Braich y Pwll. Notice how long the race at Braich y Pwll is - as the fast-flowing tide leaves Bardsey Sound and runs north, it takes a long time to slow down.

Note that it’s unlikely that all the races and overfalls that might affect a sea kayak are marked on a chart. For example, a challenging tide race can form at Maen Du at the sound end of Bardsey Sound. Although there’s nothing marked here, we might reasonably expect a race to form at such a sharp point given how fast the tide flows in this area.

In practise, there’s not a lot of difference between races and overfalls - many headlands have shallow areas extending out the sea, so that the tide is squeezed by horizontally and vertically. Many paddlers will use the terms ‘race’ and ‘overfall’ interchangeably.

Races and overfalls present a number of hazards to kayakers:

The boundary between the fast flow and adjacent slow flowing eddies can form a sharp ‘eddyline’ that can spin and capsize the inexperienced.

Turbulence as the flow accelerates, and especially as it decelerates, can form steep waves and boils.

When waves and wind move in the opposite direction to a tidal stream, larger and steeper waves will form - more on this in the notes on waves.

Of course, those with appropriate skills and experience often seek out these conditions for training and enjoyment!

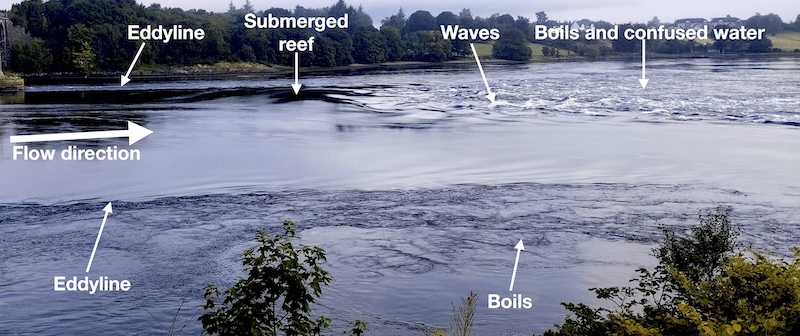

The Falls of Lora is a tidal overfall that forms at the narrow entrance to Loch Etive (so, in some sense, it’s also a race). The image below shows the Falls during the flood tide:

This overfall forms in sheltered wave, so it is rarely affected by sea state - the features are simply due to the fast flowing water.

Notice that the flow is smooth in the area where it is accelerating - all of the turbulence occurs down tide of the reef where the water is losing energy and slowing down.

It’s hard to get a sense of scale from the image - it’s likely that the largest waves in this image are a little over a meter high.

2.6.3 Signs of tidal flow

In tidal waters, it is important to understand what the tide is doing. With experience, it is possible to perceive tidal flow, perhaps by the ripples that a flow creates, or by the interaction of the tide with wind and swell. In an area of variable tide, the wind will tend to pick out areas where the tide is flowing against it with small waves, whereas regions of opposite flow can appear flat.

Tethered buoys and moored boats provide ways to assess tidal stream.

Of course, the tidal stream is often obvious from noticing which way our boats drift when we stop paddling. Transits can be used to judge this when the stream is slower.

Environmental cues can also tell us something about the height of tide: